Part II:

Japan’s frontier island

In the afternoon of Aug. 4, 2022, hours after Maja saw the great splashes in the sea off Yonaguni, then Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi confirmed that it was one of the ballistic missiles launched by China in an apparent retaliation to the visit to Taiwan by Nancy Pelosi.

Pelosi was the first U.S. house speaker to visit the island in 25 years.

Beijing considers Taiwan one of its provinces and was furious about a blatant example of what it calls U.S. “interference in China’s internal affairs.”

Beijing again launched three days of war games and patrols near the island after Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen met with U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy near Los Angeles – the first meeting of its kind on American soil, despite angry warnings from Beijing.

After Pelosi had left Taipei last August, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army fired a volley of nine missiles around Taiwan, the first one falling just kilometers (miles) from Yonaguni’s northwest coast.

Kishi said the Japanese government strongly condemned “this grave matter involving Japan's national security and the safety of its people." For the islanders, the missile splashdown was the moment they were reminded once again that what happens in Taiwan can affect Yonaguni, too.

“Yonaguni is a small island, also a border town. The government needs to protect it but also to develop a good relationship with China. Otherwise, we’re stuck,” Maja said.

Marlin fishing suffers

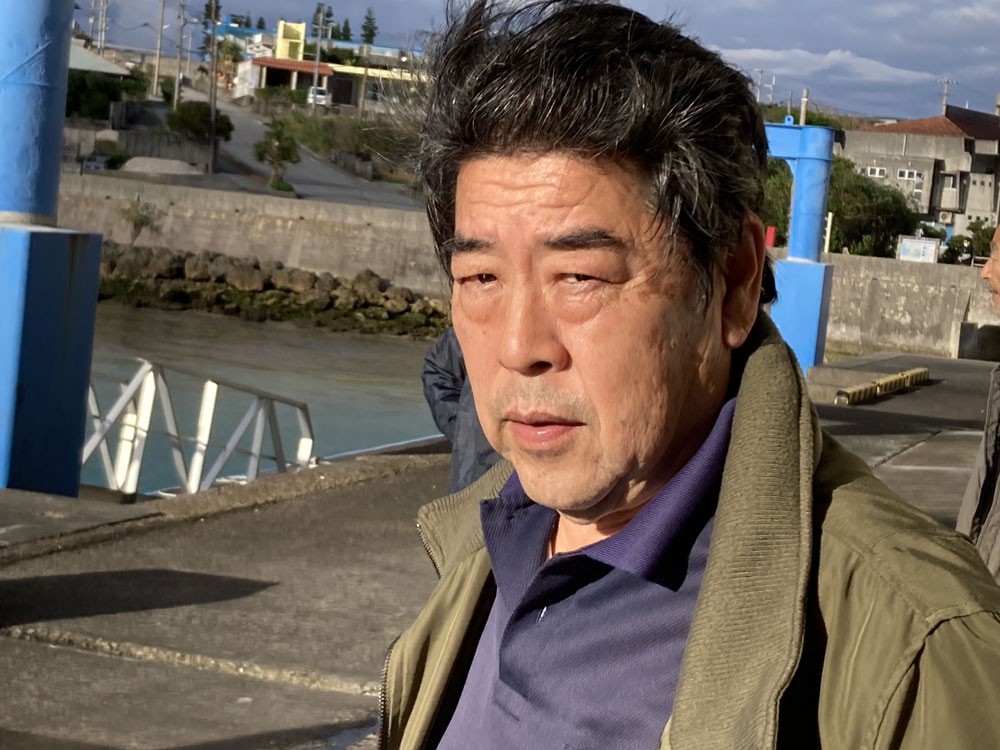

Shigenori Takenishi is a busy man.

The 60-year-old head of the Yonaguni fishing cooperative can be seen every day at Kubura fishing port, either doing paperwork in his tiny office, greeting incoming fishermen or helping out in the kitchen of the cooperative’s restaurant.

Today, a fishing boat brought back its single catch, a 25-kilogram (55 -lb) marlin that is deemed by everyone “a mere baby.”

The fish is a specialty of Yonaguni and the town holds regular annual marlin fishing competitions. But now, as tensions grow around Taiwan, their traditional marlin fishing ground in the west becomes increasingly off-limits because of safety concerns.

“Since the Chinese missile incident last August, our fishermen became really worried,” Takenishi said, poking disapprovingly at the fish’s belly.

Yonaguni fishermen have already been practically booted out of the waters near Senkaku islands in the north, which are under Japan’s control but China also claims and sends coast guard vessels to patrol.

“If the instability continues, or if China invades Taiwan, it will be a big problem for us,” Takenishi said.

Okinawa suffered some of the Allied Forces’ fiercest battles against a retreating Japan in the closing months of World War II. It still hosts around 26,000 U.S. military personnel on 31 U.S. military installations and training sites, about 70 percent of all American facilities in Japan.

Yonaguni largely escaped fighting, sustaining a couple bombing raids in 1944 and 1945 that killed some 30 islanders.

Many residents nowadays fear that the worst is yet to come with China’s aggressive posture and military ambitions.

“In recent years there have been a lot of discussions [in Yonaguni] about the situation in Taiwan and the need to boost a Japanese military presence in the island,” said Takenishi, who is also a town assembly member.

Takenishi and fellow assembly member Toshio Sakimoto, a liquor distiller, recently requested the central government help set up evacuation shelters on the island as soon as possible.

‘We were not prepared’

Sakimoto, whose family has been producing the local rice liquor awamori for five generations, said Yonaguni had been “relatively quiet until last August, when Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan.”

In February, Takenishi, Sakimoto and other local council members met with Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada in Tokyo on behalf of Yonaguni residents.

“If an emergency occurs in Taiwan, the lives and safety of the town’s people will be threatened,” they said, urging the government to come up with an evacuation contingency for islanders.

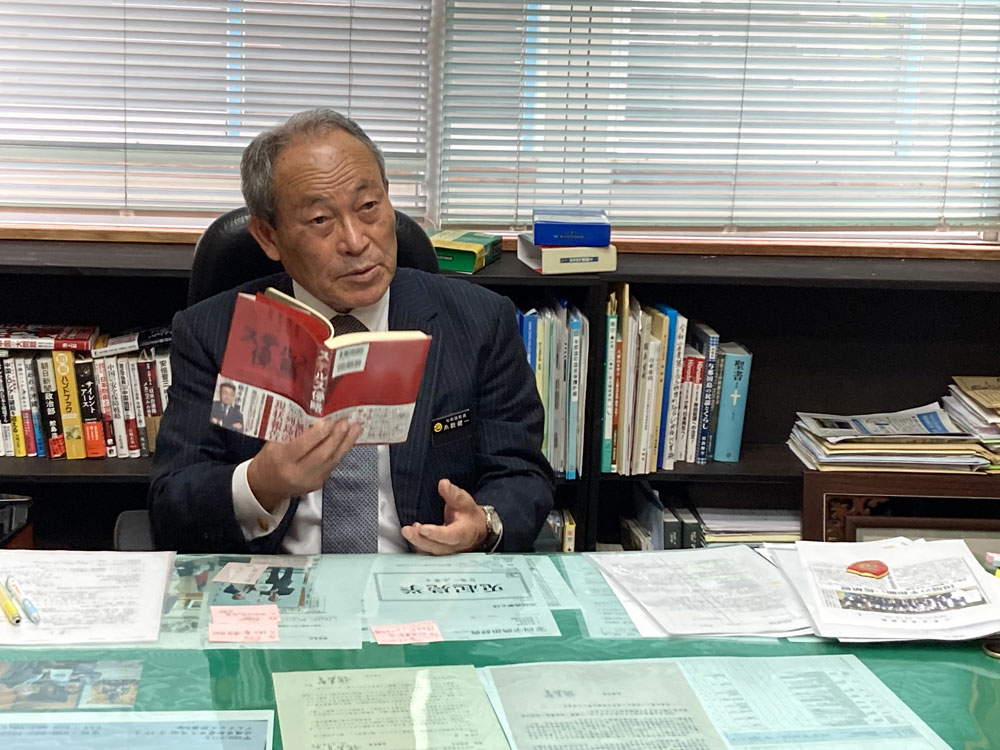

Kenichi Itokazu, the mayor of Yonaguni, confirmed that the proposal for evacuation shelters has gone to the Japanese Diet, the national parliament in Tokyo, and he will attend hearings about it.

“I don’t think it’s realistic to have shelters for every home on the island because we don’t have the time nor budget for that,” Itokazu said.

The mayor admitted that the local government was slow because “up until recently we still thought that as the economic situation in China improved, they’d become friendlier to us.”

“We were not prepared.”

The town office did take part in an evacuation drill held by the Japanese Cabinet Secretariat in December. During the exercise, residents were rushed into a community building to take shelter from ballistic missiles.

They were told missiles fired from the east would take around 10 minutes to reach Yonaguni so they should “evacuate as fast as if it was a tsunami.”

Still, many people feel that the contingency plan is far from adequate.

Kiyomi Takemasa, a former resident of Yonaguni who has settled in Ishigaki, said that the island is not self-sustaining.

“Even in Ishigaki, a much bigger island, our shop shelves become empty after a few days of bad weather when ships can’t come.”

Mayor Itokazu said ideally, he wants to be able to evacuate all civilians from Yonaguni in a crisis.

“I want to bring not only my family but everyone from here to some safer place without leaving anyone behind.”

“Fleeing the island to somewhere else would be the best,” agreed Shigenori Takenishi from the fishing cooperative.

“But we don’t have many places to run.”