On Feb. 11, Hun Sen, Cambodia’s de-facto ruler, claimed that the authorities had weeks ago uncovered a plot to kill him at his provincial mansion using drones.

One person was apparently arrested, Hun Sen said, but others may still be at large.

Who knows whether it is true or not?

Some people suspect it’s a conceit by Hun Sen, the former prime minister who handed power to his eldest son in 2023, to justify his incoming law that will brandish political opponents as “terrorists”, in an attempt to deter foreigners from aiding the exiled opposition movement.

Speaking about the alleged plot on his life, Hun Sen connected the two: “This is an act of terrorism, and I’d like to urge foreigners to be cautious, refraining from supporting terrorist activities.”

Such skepticism led one commentator, in an interview with Radio Free Asia, to claim that “ordinary citizens do not have the ability” to hit his heavily guarded Takhmao home.

In fact, they do.

Cheap drones for Myanmar opposition

Myanmar’s four-year-old civil war has shown just how much drones have revolutionized not just warfare but the balance of power between the state and the individual.

A long-range modified and armed drone costs Myanmar’s rebels around US$1,500.

By comparison, the International Crisis Group reckons second-hand AK-47s or M-16s cost US$3,000 each.

Myanmar’s military recently took delivery of six Su-30SMEs fighter jets from Russia, for which it paid $400 million -- excluding the weaponry.

As one commentator put it last year: “In an asymmetric conflict, the drone is helping to equalize the battlescape.”

Junta forces are catching up, for sure. AFP reported a few weeks ago that “the military is adopting the equipment of the anti-coup fighters, using drones to drop mortars or guide artillery strikes and bombing runs by its Chinese and Russian-built air force.”

However, the revolutionary importance of drones isn’t that a superior force will never adopt the same technology. It’s that drones -- now an irreplaceable weapon in modern warfare -- cannot be monopolized by a state.

Not for almost two centuries has there been such a technological leap in the balance of power. Not for at least the past 100 years has a dominant weapon been as cheap and available to the masses.

‘History of weapons’

In October 1945, George Orwell published a short essay that’s best known for popularizing the term “Cold War”.

“You And The Atom Bomb” also offered a take on the weapons that’s rarely reflected on these days.

Had the nuclear bomb been as cheap and easy as a bicycle to produce, Orwell reasoned, it might have “plunged us back into barbarism.”

But because the bomb is a rare and costly thing to make, it might “complete the process [of] robbing the exploited classes and peoples of all power to revolt.”

Mutually Assured Destruction would keep the peace between the nuclear states, but it meant that existing dictatorship could become permanent, Orwell feared.

How would a band of rag-tag rebels fare against a despot or imperialist prepared to quell any rebellion with a nuclear explosion?

Would the dictator who happily drops biological weapons on their own people not as easily reach for tactical nuclear bombs if they could?

Would the North Korean regime not prefer to go down in a nuclear blaze if the masses were ever to rise up?

Orwell noted that “the history of civilisation is largely the history of weapons.”

Students of history are taught that gunpowder made possible a proper rebellion against feudal power; that the musket, cheap and easy to use, replaced the cannon and made possible the American and French revolutions.

Its successor, the breech-loading rifle, was slightly more complex, yet “even the most backward nation could always get hold of rifles from one source or another,” Orwell noted.

State arsenals only

The early 20th century, however, saw the invention of weapons only available to the state and only the most industrialized states—the tank, the aircraft, the submarine and, foremost, the nuclear bomb.

Vietnamese communists, by some accounts, were peasant volunteers who battled with nothing but smuggled guns, punji traps and a clear sense of what they were fighting for, but they were able to defeat the industrialized armies of France and the United States.

In reality, the communists were well supplied with non-rudimentary weaponry by Beijing and Moscow.

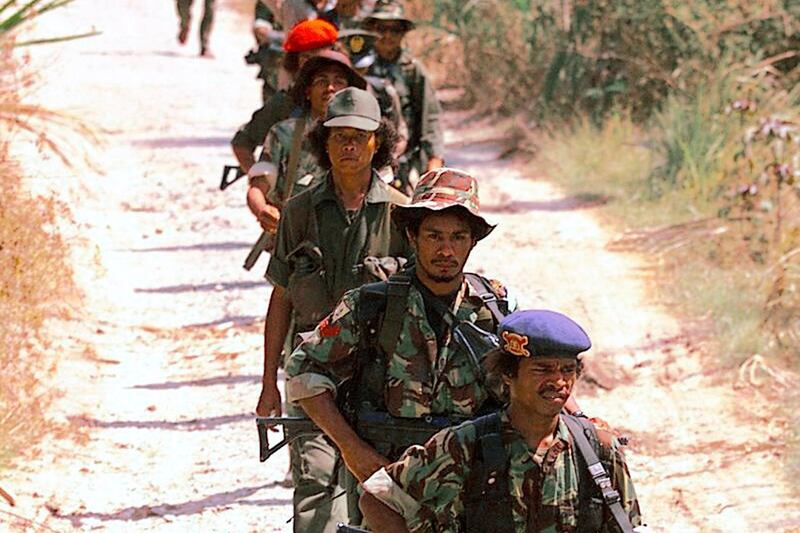

More representative of rag-tag guerrilla success were the East Timorese rebels, who had no patrons and only the most basic weapons to battle against Indonesian imperialism and its vastly superior forces.

Their stunning achievement was simply keeping their struggle alive for so long.

But the East Timorese were never going to secure independence in the jungles and hills; their victory depended on staying in the fight until international opinion turned in their favor.

Had it not, Timor-Leste would still be a province of Indonesia, as West Papuans know all too well.

RELATED STORIES

Hun Sen says drone assassination plot was recently foiled by authorities

Myanmar military adds advanced Chinese drones to arsenal

Myanmar junta chief missing from public view after drone attack

Perhaps drone warfare won’t bring victory to Myanmar’s revolutionaries.

Fighting alone doesn’t win wars. Alliances, superior industrial production, international opinion and quite a bit of luck — all are as important.

Yet without drone warfare, the junta would arguably have won this battle a lot sooner.

It probably hasn’t been lost on the Thai military that another coup might not be accepted as meekly as in earlier military takeovers by a populace which has closely observed events in neighboring Myanmar.

Intentional or not, Hun Sen’s revelation that someone apparently tried to kill him using drones has imbued him and his impregnable regime with a rare sense of vulnerability.

His family rules over a 100,000-strong military that he has instructed to “destroy... revolutions that attempt to topple” his regime, plus a loyal National Police and an elite private bodyguard unit.

One son is head of military intelligence. Another son, Prime Minister Hun Manet, was previously the army chief.

But, as despots are now realizing, all that now means a lot less in the age of the drone.

David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA.