The effective implosion of the apartheid regime in South Africa came almost a decade before the actual event.

In February 1985, Nelson Mandela was informed by his captors, after a quarter of a century of confinement, that he was free to leave Robben Island.

He rejected their pardon. He alone, he said, would choose when he left his captivity, and he would not do so merely so his captors could gratify themselves and not until all the regime’s other political prisoners had been released.

In that act, power shifted hands, and Mandela made it obvious to all that an illegitimate government couldn’t pardon him for a crime he never committed.

Remembering this, it was heartening to read that Tran Huynh Duy Thuc, a Vietnamese political prisoner “released” early from prison in late September after 16 years in confinement, had refused to accept a presidential pardon when his jailors told him that he was free to go.

“I immediately protested, saying that I was not guilty and had no reason to accept the pardon, and that I would not go anywhere,” Thuc later recounted.

It took 20 prison officers to “forcibly carry me out of the prison gate amidst protests from political prisoners there, then put me in a car and took me to [an] airport.”

He added: “I was forced to accept amnesty, an unprecedented event in this country.” To him, it was a “forced pardon.”

And he also knew why he was being released eight months early: “I became an important supporting act for the president’s visit to the U.S..”

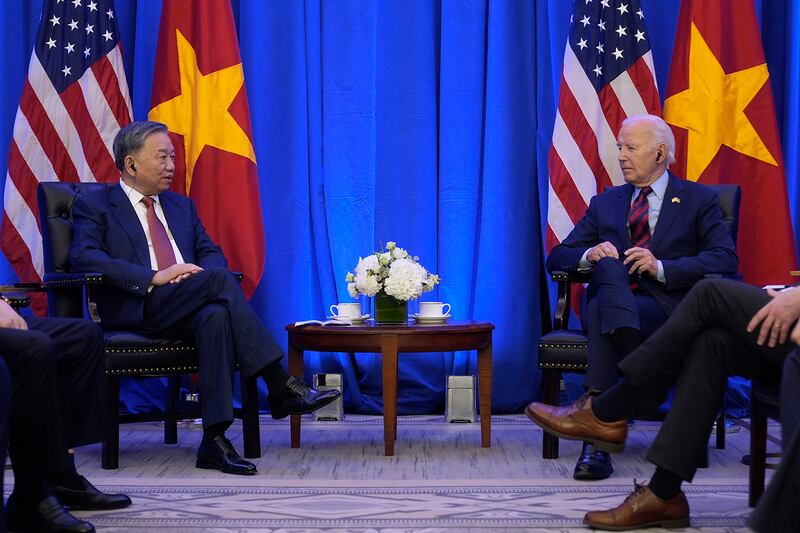

Thuc and Hoang Thi Minh Hong, a climate campaigner, were pardoned and released from jail the day before the Vietnamese Communist Party chief and then state president, To Lam, boarded a flight to New York to talk at a United Nations summit and meet Joe Biden, the U.S. president.

Down payment for Biden

Quite clearly, the prisoner releases were a down payment from the communist government in Hanoi for goodwill in New York.

The U.S. government did not directly comment on the matter, nor did the Vietnamese government officially give a reason for the releases.

But Hanoi thinks Washington likes what it sees.

Thuc and Hong were not the first political prisoners the Communist Party offered up as human gifts to appease the Americans. Some, like Tran Thi Nga, were sent off into exile in the United States after their pardon.

Perhaps Washington has made it known, at least privately, that it is pleased by these events. It hasn’t suggested otherwise.

The Vietnamese people must form their own opinion of their government trading its citizens and degrading the justice system to appease a former enemy.

This sordid deal is not what Ho Chi Minh was imagining when he said his “ultimate desire is to make our country completely independent, our people completely free.”

The exchange showed Washington’s myopia over the Vietnamese Communist Party’s oppressive behavior. Biden probably would have still told Lam in New York that “there’s nothing beyond our capacity when we work together” even without the release of a couple of political prisoners.

Washington should not be in the business of accepting prisoners from the Communist Party, whose control of the courts allows it to imprison anyone who dares challenge its authority.

Judge and jury

Being able to prosecute and then arbitrarily release prisoners for political purposes puts the Communist Party above the law, acting as judge and jury and often the sole absolver of sin.

Someone imprisoned for standing up for their rights can at least maintain their innocence against their oppressor.

But a prisoner is only released early through a pardon, and, by being forced to accept a pardon, the prisoner must at least appear to accept their guilt.

This is not an exculpation; it’s a gift of freedom from an oppressor. The Communist Party’s pardon legitimizes its earlier tyranny.

By not discouraging pardons of political prisoners and by not condemning these in the same manner as it would condemn the unfair arrest of an individual exercising their rights, the U.S. helps undermine Vietnam’s rule of law.

The U.S. would be more helpful if it were to say that it only welcomes the release of political prisoners if the Vietnamese Communist Party acquits them, not pardons them.

The Communist Party could pardon all political prisoners and empty its cells tomorrow, as some demand, but that act will make it easier to double the prison population the next day.

Only the proper rule of law would prevent that. And Washington must not allow that to be debased by Vietnam to boost bilateral relations.

David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. He writes the Watching Europe In Southeast Asia newsletter. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA.