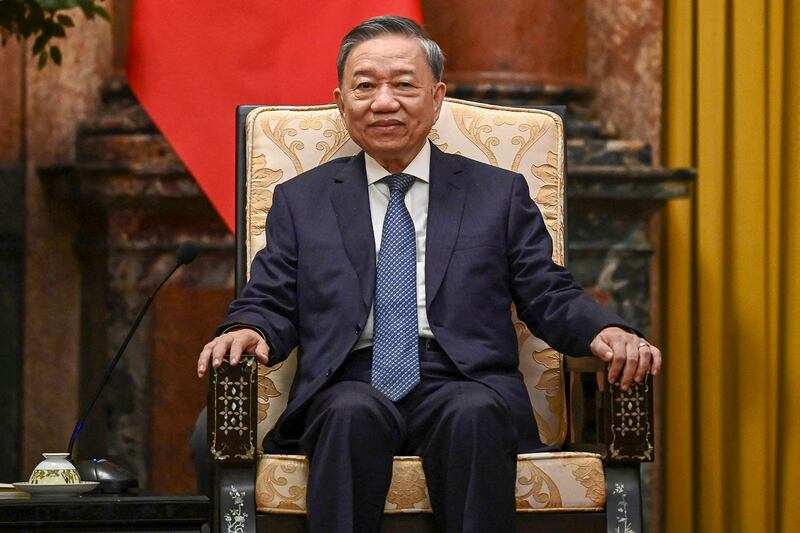

When To Lam was elected general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam in August, there was much speculation that the former top cop would reorient Vietnamese foreign policy towards China.

Lam shares his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping’s fear of popular “color revolutions” and cracked down hard on dissent in his years as a minister of public security. But there has been no re-ordering of Vietnamese foreign policy, nor will there be.

Foreign policy is set by the CPV’s Central Committee, and was further codified in the 2019 Defense White Paper, which said “depending on circumstances and specific conditions, Vietnam will consider developing necessary, appropriate defense and military relations with other countries.”

More importantly, Vietnam’s studiously non-aligned foreign policy has been very good for the country and its leaders are masters of the art of balancing.

Within three days of Minister of National Defense Phan Van Giang’s historic trip to the United States, where he met Secretary Lloyd Austin, he was in Beijing at the Xiangshan Forum, meeting with his Chinese counterparts.

Lam's first trip as general secretary to China was seen as evidence of a tilt. But the trip had been pre-planned and followed an established pattern.

Elected president in May, Lam made his first trips to Laos and Cambodia, which is the norm for Vietnamese leaders. China is almost always the third visit of a top leader.

To Lam’s visit to the United States to attend the United Nations General Assembly again put Vietnam’s non-aligned foreign policy on full display.

While he did not make a side trip to Washington D.C., which was a missed opportunity, it was an important signal to China.

Lam certainly kept busy in New York, speaking at the UN General Assembly, Columbia University and the Asia Society.

Nothing new was in any of the speeches, which delivered the same Vietnamese diplomatic talking points and catchphrases that one would expect from any Vietnamese leader. They offered nothing new in terms of policy proposals, nor suggested a new wave of economic reform or liberalization in Hanoi.

Hanoi’s Russian dilemma

Perhaps most surprising was how insecure Lam seemed during question and answers. The former top cop is a sharp guy, yet he read canned answers to generic questions from his briefing book.

Lam had a brief meeting with President Joe Biden on the sidelines of the UNGA, sessions that are the diplomatic equivalent of speed dating. The two sides reaffirmed their commitment to developing the comprehensive strategic partnership that was reached a year previously during Biden's visit to Hanoi.

Lam pushed for the awarding to Vietnam of market economy status, a designation which the U.S. Commerce Department rejected in September.

While the Vietnamese had made market economy status as a diplomatic priority, they were naïve to think that it would be awarded in the midst of a hotly contested U.S. presidential election, in which votes in critical swing states with large manufacturing sectors could determine the outcome.

Perhaps Lam’s most important meeting in New York was with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

While Vietnam claims to have a neutral foreign policy, their policy towards Ukraine has been abysmally bad. Vietnam has continued to engage Russia at the highest levels, hosting Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in July 2022, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in March 2023, and President Vladimir Putin in June.

Vietnam has painted itself into a corner as Putin continues to assert that Ukraine is a part of Russia and deny any sense of Ukrainian nationhood. This sets a very dangerous precedent for the Vietnamese, who were themselves a Chinese province for over a thousand years.

For a country committed to upholding the rules based international order, Vietnam has turned a blind eye to Russia's naked aggression and determination to change borders through the use of force.

But Vietnam’s military remains very close and dependent on Russia. Despite attempts to diversify their supply chains, Russia remains the single largest source of weaponry in Hanoi’s arsenal.

With an annual budget of around $9 billion dollars, Hanoi sees Russian arms as cost effective, and many are produced by Vietnam under license.

Moreover, in 2023 the two sides inked an agreement that would transfer profits from a Siberian joint venture to fund the purchase of the next generation of Russian arms – a pact designed to evade U.S. sanctions.

While Lam had some important engagements with the U.S. business community, especially with the leaders of high tech firms, he didn’t seal any major investments.

Despite ambitions for their AI and chip fabrication, there are real limitations and structural impediments that Vietnam needs to address. These include a scarcity of technically proficient workers, electricity shortages, slow government policy implementation and corruption.

Communist nostalgia, balance

The most significant Vietnamese meeting in New York was that of Minister of National Defense Phan Van Giang with the UN Office of Peacekeeping Operations.

Vietnam currently has three deployments to UN operations in Africa, including an engineering battalion and a field hospital. Vietnam recently dispatched 240 peacekeepers to Abyei in South Sudan to replace personnel, a sign of its commitment to UN peacekeeping and support for multilateralism.

But rather than looking to the future and traveling to Silicon Valley or another high-tech hub for meetings with investors, Lam opted for nostalgia for the communist past with a state visit to Cuba.

Economically, the Havana visit was nonsensical. There was $111 billion in bilateral trade between the U.S. and Vietnam in 2023. With a mere $155 million in trade with Cuba, Vietnam is Cuba’s second-largest trading partner, and the largest foreign investor in Cuba from Asia.

But this trip was important for Vietnam.

In part this is Hanoi’s diplomatic reassurance to China that its foreign policy is not only neutral – with Lam not spending more time in the United States or Canada – but also socialist in its orientation. This responds to a constant admonishment from Beijing.

While there is no economic logic to the visit to Cuba, there is a historical and emotional one, reflecting Vietnam’s gratitude for Havana’s support during its long war against the United States and taking place ahead of the 65th anniversary of diplomatic ties.

And the Vietnamese are nothing but nostalgic for Fidel Castro, who not only visited Vietnam in 1973, but traveled to a “liberated zone" in Quang Tri, South Vietnam, the only foreign leader to do so.

Lam’s global travels have not let up.

He traveled to Mongolia and Ireland for state visits, before flying to France for an official visit and to attend the 19th Francophonie Summit. It was the first visit by a Vietnamese head of state to France, its former colonial master, in 22 years.

There is little economic rationale for the visit to Mongolia, where a handful of minor agreements including a comprehensive partnership were concluded.

While bilateral trade with Ireland was roughly $3.5 billion in 2023, there is potential to grow, and Ireland has a vibrant high tech sector and investment climate. Ireland is a minor player in Vietnam, with some 41 small projects with $61 million in total capital.

Back in Hanoi, rumors of party infighting and demands that Lam relinquish the presidency at the National Assembly session this month abound.

Although he seems to be making the most of his time abroad, Lam is signaling that Vietnam’s foreign policy remains non-aligned, even as Chinese aggressive actions in the South China Sea merit unusually blunt responses from Hanoi.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or Radio Free Asia.