The family of ethnic Mongolian dissident and Nobel Peace Prize nominee Hada say they have been prevented from visiting him in a hospital in China’s northern region of Inner Mongolia, after he was rushed there for emergency treatment while under house arrest.

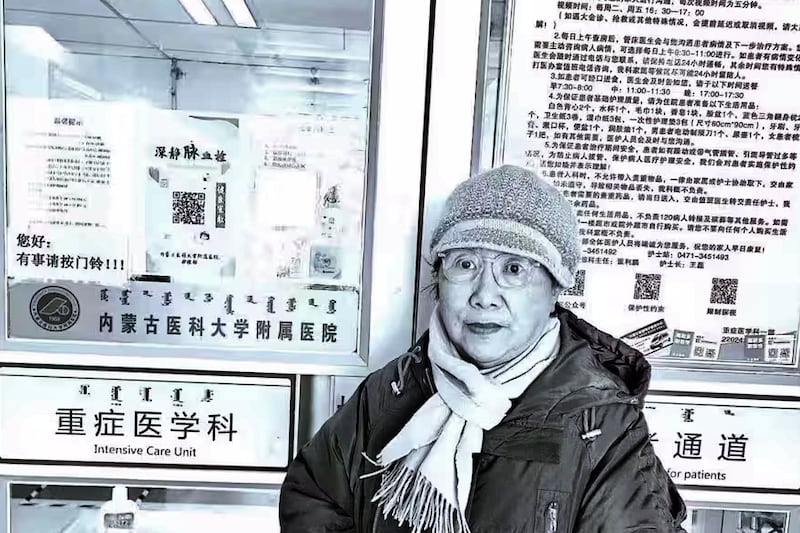

Hada, 69, was admitted to the Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University on Jan. 25, where he spent some time in a critical condition, his wife Xinna told Radio Free Asia on Monday. Hada, Xinna and their son Uiles all go by a single name.

Hada’s hospital stay could be linked to his recent nomination for the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize by Japanese lawmakers, who cited his continuing advocacy for his people living under Chinese Communist Party rule despite years of persecution.

Now, the authorities, including medical staff at the hospital, have stopped updating Xinna and the couple’s son Uiles from Feb. 6, after releasing Hada to a general ward from the intensive care unit, or ICU, Xinna told RFA in a recent interview.

“The state security police called Uiles [on Feb. 6] and said [Hada] needs clothes, so Uiles and I went to the hospital and waited there for a long time,” Xinna said in an interview on Feb. 7. “Then two state security police officers came in and said, ‘Don’t go in,’ and left.”

Medical staff at the ICU told Xinna and Uiles that Hada had been sent to a general ward on the morning of Feb. 6, she said.

“I asked which department, and the doctor said the police won’t allow me to tell you that,” she said.

Whereabouts unknown

Xinna said she is worried because she no longer knows Hada’s whereabouts.

“Now we don’t know whether Hada is in the hospital or not,” she said, adding that the blocking of family contact could be linked to RFA’s reporting of Hada’s Nobel Peace Prize nomination.

“They don’t want the outside world to get involved,” Xinna said.

“As a family member, I am very angry about this,” she said. “Hada has been in jail or under house arrest for 30 years now, and he is so sick now.”

“We have the right to visit him, but we are not allowed to see him ... now he’s been cut off from any contact with the outside world,” she said.

RELATED STORIES

Ethnic Mongolian dissident Hada gets Nobel Peace Prize nomination

Ethnic Mongolian dissident Hada rushed to hospital from house arrest

China recruits Mandarin-speaking teachers to move to Inner Mongolia

Digger plows into grasslands protesters in China, injuring ethnic Mongolian herder

Overseas-based ethnic Mongolian activist Khaas, who also goes by a single name, said the timing of the ban on contact was suspicious.

“He was hospitalized after the news broke that he had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, but the authorities haven’t disclosed what illness he has or how serious his condition is,” Haas said.

“Now he has been transferred to a general ward, his condition still hasn’t been disclosed, and nobody knows what’s happening,” she said, adding: “It’s inhumane to prevent him from seeing his family.”

House arrest

The Nobel Peace Prize nomination was made by lawmakers Hiroshi Yamada, a member of the House of Councillors, and Yoichi Shimada, a member of the House of Representatives.

Hada, who was incarcerated for 19 years for his activism on behalf of ethnic Mongolian herding communities, remains under house arrest in the regional capital Hohhot.

Xinna has also helped ethnic Mongolian herders petition authorities and find lawyers to fight their claims to their traditional grazing lands that are increasingly being taken over by Han Chinese migrants or state-owned companies.

Hada was released from extrajudicial detention in December 2014, four years after his 15-year jail term for “separatism” and “espionage” ended, but he has remained under close police surveillance and numerous restrictions, including a travel ban and frozen bank accounts.

Hada has taken issue with his alleged “confession,” to the charges, saying that it was obtained under torture and after being given unidentified drugs.

He has also said he expects to stay locked up for as long as the ruling Chinese Communist Party remains in power.

Ethnic Mongolians, who make up almost 20 percent of Inner Mongolia’s population of 23 million, increasingly complain of widespread environmental destruction and unfair development policies in the region.

The authorities have also phased out the Mongolian language in favor of Mandarin as a medium of instruction in schools — a policy that sparked mass protests by parents and students followed by a regionwide crackdown when it was first announced in September 2020.

Clashes between Chinese state-backed mining or forestry companies and herding communities have been common in the region, which borders the independent country of Mongolia.

Hada has described the routine evictions of herders from their traditional grazing lands, often in the name of ecological protection, as part of a calculated program of “ethnic cleansing.”

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Roseanne Gerin.