WASHINGTON - In a world bracing for a close U.S. presidential election result this week, a large swathe of Asia picks its leaders without suspense -- and mostly with little popular participation.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping was confirmed by the National People’s Congress in March 2013 with 2,952 votes for, one against, and three abstentions. Last year the rubber stamp parliament voted unanimously to give him a third term, putting him on track to stay in power for life.

North Korea’s leaders have inherited their power from father to son for three generations. They are technically “elected” – but there is no choice. In 2014, Kim Jong Un was elected to the Supreme People’s Assembly without a dissenting vote with 100% turnout.

A leadership succession that played out in Vietnam this year saw a serial purge of political rivals and the death of an ailing top leader propel To Lam, a wily career security policeman to the top of the Communist Party, where he is maneuvering for a key intra-party vote in early 2026.

In U.S. elections, the president and vice president are not elected directly in a popular vote by citizens. Instead, they are chosen through the Electoral College process, in which electors equal to the total number of representatives and senators a state has in Congress cast that state’s votes. These electors vote according to the majority of residents in that state.

Members of Congress – 100 in the Senate and 435 in the House of the Representatives – are elected directly by residents of each of the 50 states.

How do the Communist-ruled countries in Asia choose their leaders?

Of the six countries covered by Radio Free Asia, whose mission is to provide independent media to territories that lack it, four – China, North Korea, Laos and Vietnam – were founded and organized on the Marxist-Leninist party-state model copied from the Soviet Union.

Some countries call themselves “democratic,” but in practice the people have little or no say in choosing their leaders or governments.

NORTH KOREA

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was founded in 1948 by Kim Il Sung, who had been cultivated by Moscow as a Cold War ally in the northern half of Korea.

North Korea describes itself as an “independent socialist state” with universal and compulsory suffrage at 17, and holds elections for the Supreme People’s Assembly, the national legislature every four-to-five years, and for local People’s Assemblies every four years.

In practice, each candidate is pre-selected by the North Korean government and voters are allowed to vote either “yes” or “no” in ballots that are not private. Nearly all elections report 100% support for the government.

CHINA

The People’s Republic of China, founded in 1949 by Mao Zedong, describes itself as a “socialist democracy and a people’s democratic dictatorship.” Xi-era slogans describe it as “socialist consultative democracy” and “whole-process people’s democracy.”

China has universal suffrage from age 18, with voting at five levels of People’s Congresses, from local townships to cities and provinces, to the parliamentary National People’s Congress. Higher-level Congresses are indirectly elected by delegates of lower-level Congresses.

Technically not a one-party state, China has eight non-communist parties, including the Revolutionary Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang, the China Democratic League, the China National Democratic Construction Association and the China Association for Promoting Democracy.

However, as the U.S.-based Freedom House notes, “the CCP effectively monopolizes all political activity and does not permit meaningful political competition.” The noncommunist parties serve in an advisory role, “but their activities are tightly circumscribed, and they must accept the CCP’s leadership as a condition for their existence.”

VIETNAM

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam, founded in 1975 after Ho Chi Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) overthrew the U.S.-backed Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), likewise followed the Soviet template of one-party politics.

Suffrage is universal at age 18, and direct elections are held for local People’s Councils and the National Assembly -- but all candidates are pre-approved by the ruling party.

“Vietnam is a one-party state, dominated for decades by the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam,” says Freedom House. “Although some independent candidates are technically allowed to run in legislative elections, most are banned in practice.”

In the May 2021 elections for 500 National Assembly seats, the Communist Party of Vietnam took 97.2% of the vote, while non-party candidates got 2.8%. The next election is in early 2026.

LAOS

In the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, a Communist protégé of Vietnam also founded in 1975, “is a one-party state in which the ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party dominates all aspects of politics and harshly restricts civil liberties,” says Freedom House.

Laos has universal suffrage, and its president, vice president, and prime minister are elected by the National Assembly. These elections, however, have been deemed not free or fair, and in the most recent 2021 poll, the ruling party took 158 of the body’s 164 seats, with the rest going to pre-approved independents.

“The electoral laws and framework are designed to ensure that the LPRP, the only legal party, dominates every election and controls the political system,” says Freedom House.

CAMBODIA

Radio Free Asia’s other target countries are Cambodia and Myanmar, more pluralistic states that have held competitive, if flawed elections.

Cambodia has been holding elections since 1993, as mandated by the 1991 Paris Agreements, which ended the country’s civil war and mandated democratic elections under a parliamentary constitutional monarchy.

In practice, however, Cambodia’s political system has been dominated by the Cambodian People’s Party and its leader Hun Sen. A strongman who violently refused to share power with coalition partners in the 1990s, Hun Sen ruled the country for more than three decades until handing power last year to his son, Hun Manet, but still wields great influence.

“While the country conducted semi-competitive elections in the past, polls are now held in a severely repressive environment,” says Freedom House, noting Hun Sen’s penchant for banning popular opposition parties.

The July 2023 National Assembly elections, held just a month before Hun Manet took over from his father, were condemned by the United States, the European Union and the United Nations as neither free nor fair.

MYANMAR

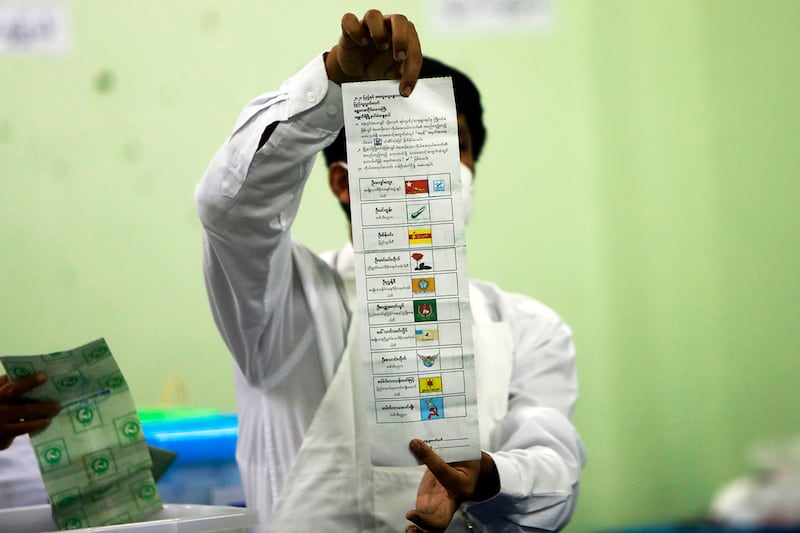

In November 2020, the country formerly known as Burma emerged from only its third semi-competitive election since its independence in 1948, a vote that delivered a strong majority to the National League for Democracy, or NLD, of de facto national leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

The multi-party election, which observers widely deemed credible despite flaws with conflict zone voting cancellations and registration, delivered 86 percent of the seats in the Assembly of the Union to Suu Kyi’s NLD, routing the army-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party.

On Feb. 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military, citing baseless claims of election fraud, deposed State Counsellor Suu Kyi and President Win Myint in a coup d’etat, later jailing them.

The junta annulled the results of the 2020 vote, and pledged to hold elections in 2023 – but has repeatedly delayed this and extended its emergency rule as the nation became more deeply embroiled in a civil war that has killed thousands and destroyed wide swathes of the country.

The military regime has committed to holding a general election late next year, with voting to be staggered because of security concerns, but has continued to extend a state of emergency across the country and brought in tough new registration laws that disqualify many parties from standing.

TIBET

Chinese-run “autonomous” regions such as Hong Kong, Tibet and Xinjiang largely follow mainland practices. But Tibetans who followed the Dalai Lama when the spiritual leader fled into exile in India and other countries around the world in 1959, and their descendants, have been choosing their leaders.

In 2021, Tibetans living outside of their China-ruled homeland held their third election since 2011, to seat a new political leader, or sikyong, for their India-based government-in-exile called the Central Tibetan Administration.

Penpa Tsering won the CTA’s leadership in a vote among the Tibetan diaspora, a community of about 150,000 people living in 40 countries, mainly India, Nepal, Europe and North America.

Edited by Malcolm Foster.