In the decade since the U.N. first launched its International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, nearly 800 journalists have been killed across the globe. Many more have faced violence, threats, harassment and lawfare, with the perpetrators often going unpunished.

This is the situation in war zones like Myanmar, where journalists find themselves trapped in crossfire. But it is also true in ostensibly peaceful countries. China remains the world’s largest jailer of journalists; Cambodia has seen reporters assaulted for trying to expose wrongdoing; and, just this week, Vietnam sentenced a blogger to 12 years in prison in a case many believe to be retaliation for his reporting on corruption.

RELATED STORIES

Cambodian journalist freed on bail after apology over posts

For Burmese journalist, an uneasy safety in Thailand

Chinese court rejects feminist journalist Sophia Huang’s appeal

Vietnam jails journalist for 7 years for ‘propaganda’

Journalists dismiss official claims of press freedom in Hong Kong

In China, drones, social media monitor foreign journalists: report

On Wednesday, the New York-based press freedom nonprofit Committee to Protect Journalists released its annual Global Impunity Index. Asia was the most represented region, with the Philippines and Myanmar ranked 9th and 10th among countries where the murders of journalists go unpunished.

During the past year, Radio Free Asia and its sister publication BenarNews reported on a number of cases of journalists who faced retribution for doing their job. Some were assaulted, one was abducted and several were handed stiff prison sentences. For those in the most closed regimes, meanwhile, 2024 simply represented the year in which families learned the fate of those silenced much earlier. Below is a roundup of recent cases in RFA and BenarNews coverage areas.

Vietnam

ON OCT. 30, journalist Duong Van Thai, 42, was tried in Hanoi for creating “propaganda against the state” in violation of Article 117 of the penal code, a vaguely written law that rights organizations have said is often used by Hanoi to silence dissent. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison, in a trial held behind closed doors and with even his family barred from attending.

The trial came more than 18 months after the blogger and YouTuber disappeared from his home in Bangkok, where he had fled and sought political asylum in 2019. Rights monitors believe Thai was abducted, with many condemning both Hanoi and Bangkok for their role in mounting transnational repression.

Thai was known for his searing political commentary, including reporting on corruption and political infighting — work that many believe made him a target. “Thai’s work exposing corruption is not a crime—it’s a critical exercise of free expression, essential to accountable governance,” campaign group PEN America wrote on X shortly before his sentence was announced.

Myanmar

JOURNALISTS Htet Myat Thu, 28, and Win Htut Oo, 26, were shot dead by junta soldiers on August 21, 2024 in Mon state. The pair were killed when soldiers raided Htet Myat Thu’s Kyaikto township home, after reportedly receiving a tip that revolutionary forces were stationed there.

Htet Myat Thu reported for local news outlet The Voice, and had been arrested years earlier while covering an anti-coup protest. Win Htut Oo reported for DVB and The Nation Voice, two more popular local news outlets. At least five journalists have been killed and more than 170 arrested since the Feb. 2021 military coup.

“Journalists are working on the ground and trying to deliver the true news on time. The junta army regarded this work as an attack on them, and treated the journalists badly,” explained Nay Aung, editor-in-chief of The Nation Voice. A resident who wished not to be named for security reasons, said that the junta forces cremated the two journalists’ bodies instead of returning them to their families.

Bangladesh

AT LEAST five journalists were killed and scores injured amid unrest that turned to violence this summer in Bangladesh. Sharif Khiam Ahmed, a reporter for RFA’s sister news organization BenarNews, was beaten by protesters, who hit his head with a brick, while Jibon Ahmed, a contributor to Benar, was struck by pellets shot by security forces.

Even those outside the countries faced personal attacks. After doing live broadcasts from the Washington newsroom about the events in Bangladesh, Benar newscaster Ashif Entaz Rabi was targeted by Nijhoom Majumder, a well-known activist for the ruling Awami League party with more than 265,000 Facebook followers.

Rabi was named, pictured and accused in a Facebook post and separate Facebook video of having been assigned by the CIA to “broadcast false news” and “spread false rumors” in a US-funded plot to “overthrow the government.” These posts disappeared shortly after the fall of the Sheikh Hasina government in early August.

Indonesia

VICTOR MAMBOR —a Jayapura-based stringer for BenarNews — and his Papua-based media outlet Jubi are known for covering rights abuses in Indonesia’s militarized and restive Papua region. That has frequently brought them in the crosshairs of violence.

In early October, Molotov cocktails were thrown at the Jubi editorial office in Jayapura, igniting a fire between two parked vehicles. The police said they are investigating, but no perpetrators have yet been found, and rights groups note that attacks on the media in Papua often go unpunished.

“If left unsolved, the public will wonder who is behind it,” explained Gustaf Kawer, director of the Papua Human Rights Lawyers Association. “I believe it is essential to clarify the perpetrators to prevent future incidents and ensure that the press can operate freely.”

The attack was not the first for Mambor. In Jan. 2023, a bomb exploded outside his residence and in April 2021, his car windows were smashed and vandalized, with no arrests ever made.

China

IN THE MIDDLE of the day on Nov. 17, 2023, police entered the Nanjing home of dissident journalist Sun Lin; neighbors reported the sounds of a struggle. The police brought him to the hospital and by evening was pronounced dead, with the overseas-based Chinese Human Rights Defenders network saying he appeared to have been beaten to death.

Lin, who used the pen name Jie Mu, was known for his social justice coverage and had served two four-year prison terms on charges related to his work and outspoken commentary. Police have since tried to claim they were defending themselves after being attacked by the journalist, according to overseas-based dissident Sun Liyong.

“Sun Lin is nearly 70 years old, so how would he be able to beat up a group of young men?” he said. China ranked 172 out of 180 countries on this year’s World Press Freedom Index from Reporters Without Borders, which notes it is the “largest prison for journalists.”

Uyghur

IN CHINA’S Western Xinjiang region, suppression of Uyghurs has been so complete that virtually no independent or citizen journalists outside state control remain working in the region. Though the mostly Muslim ethnic minority makes up only around one percent of China’s population, nearly half of the nation’s imprisoned journalists are Uyghur, according to Reporters Without Borders.

Given the extreme repression by Chinese authorities in the region, it often takes years for Uyghurs outside the country to learn the whereabouts of family members and colleagues. In May, Voice of America journalist Kasim Kashgar learned that five former colleagues of his had been sentenced in 2021 to seven years in prison because of links to him.

The 2018 arrest of publisher Erkin Emet was only uncovered in March. Qurban Mamut, an influential Uyghur editor and the father of Radio Free Asia journalist Bahram Sintash, was arrested in 2017.

Earlier this year, Sintash told the Committee to Protect Journalists he had little doubt that Mamut’s 15-year-prison sentence was in response to his work editing the influential magazine Xinjiang Civilization. “Many of the members on the board were subsequently taken to re-education camps, including my dad,” he told CPJ.

Cambodia

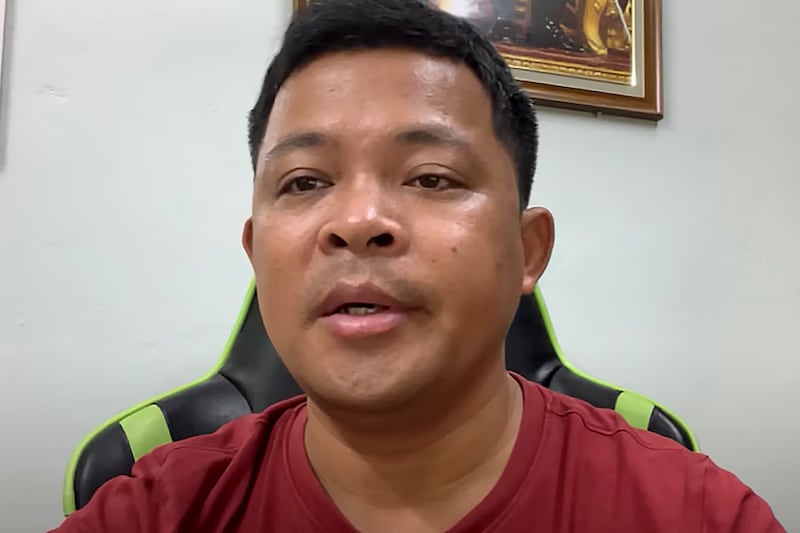

ON MARCH 2, Loun Phearin, a journalist who runs a small online website called Sameang Hot News, showed up at a location in Poipet where there had been reports of illegal gambling. As he and his team got ready to host a livestream, a group of men approached the journalists and began attacking them with sticks and rocks.

“Three people were hospitalized,” he told RFA this month. “There are so many of them [the attackers].”

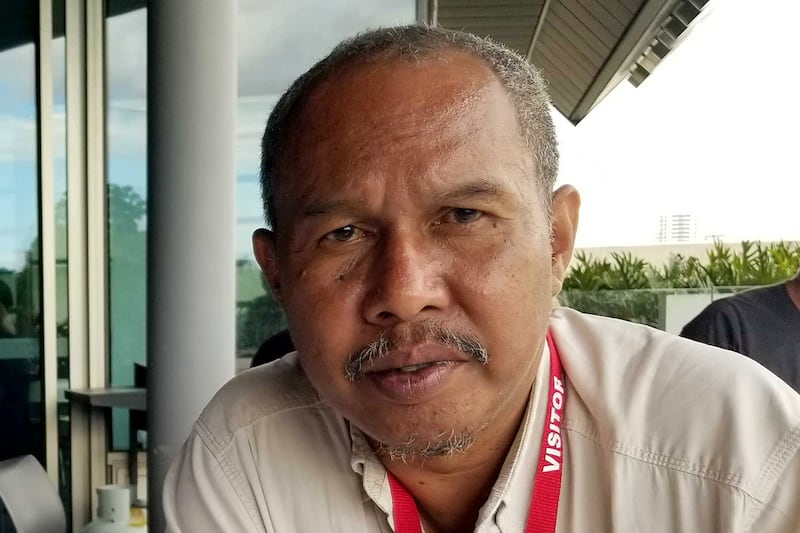

No arrests have been made, but Phearin and his colleagues have been sued by the owner of the gambling venue for trespassing. Nop Vy, executive director of the Cambodian Journalists Alliance Association that the case is just the latest in a long line of attacks against reporters that have gone unpunished.

“If this case is not resolved or the perpetrators are not prosecuted, it may be an incentive for others to commit crimes against journalists,” he said.

Hong Kong

IN SEPTEMBER, the prominent journalist Chung Pui-kuen was sentenced to 21 months in prison — making him the first journalist to be imprisoned for sedition since the 1997 handover. Chung’s co-defendant, Patrick Lam, received an 11-month sentence, allowing him to be released immediately.

Chung had spent decades building up his career in Hong Kong’s media industry and was known for his investigative journalism and focus on political and social issues, especially those related to civil rights and democracy in Hong Kong. At the time of his arrest, he was editor-in-chief of the now-defunct Stand News, while Lam was the acting-editor-in-chief.

Both spent almost 12 months in jail following their arrests in December 2021 and faced a 54-day trial this year during which lawyers for the Hong Kong government accused Stand News of promoting “illegal ideologies” and smearing the security law and the police who enforced it.

For observers of Hong Kong, the case reflected the rapid decline in the city’s once-robust free press since Beijing imposed a controversial national security law in 2020. A decade ago, Hong Kong ranked 61 among 180 countries on RSF’s World Press Freedom Index. This year, it ranked 135th.